#281: All I Wanna Do

…is puke really. The history of music is littered with people who, put simply, just didn’t belong there. They might have been crazy bastards, plagiarists, paedos or simply untalented to the point where they just weren’t that entertaining. You can decide in which category Collette fits into, but, in order to help you, she just wasn’t that talented. I doubt she was crazy, had a paedo bear or plagiarised anyone.

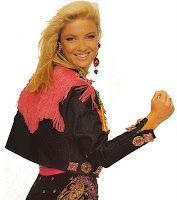

Collette ‘exploded’ onto the scene in 1989 with her ‘remake’ of Anita Wards brilliant Ring My Bell. Whereas Anita Ward could sing the shit out of anything she chose to, Collette’s fame was packaged more around her fluro bike pants, braces and lyrca, into which she crammed a pair of rather large norks (bashed into a bra one size too small) and a bigger snout that wasn’t immediately apparent until she turned side on and aerobic exercises that she passed off as dance routines along with some absolutely mental poses that she struck. In a way she foreshadowed virtually every musical act that’s on the idiot box these days, where the emphasis is on Zuma routines and any vocal ability is decried from the balconies. Who gives a shit if they can sing? Do they have big tits and can they dance like a slut in heat? If the answer is yes then they’ll hit the top of the charts. Even when a genuine vocal talent such as Mariah Carey discovered that her voice wasn’t enough to ensure longevity and success, she had to get her nay-nay’s enlarged and her clothing reduced and basically put it about like a four dollar hooker. God love her, I still like listening to Vision of Love though, although these days she’s more a Vision Of Skank. However, unlike Carey and a few others, Collette had a voice that could be best described as weedy, and at worst, horrid. She wasn’t BOBFOC* by any stretch of the imagination, but jeez…I dunno.

Collette recorded two albums, one of which made the Top 50 nationally, the other of which died a death that’d have made Phil Spector proud. However, and this might stun some people, whereas her first single, the excruciating Ring My Bell hit number 5 on the charts, her follow-up, the equally as bad All I Wanna Do reached number 12! From there her career entered freefall and, God love the girl, she now works at Taronga Zoo where people walk past her and ask if she’s THAT Collette. The answer is, of course she is. And no, before you ask, she’s not an exhibit, that’d be far too cruel, both the for the zoo and Collette herself.

While Collette isn’t largely forgotten, the lawsuit over her is. Yes, there was a legal battle over the career and earnings of Ms Roberts in 1989, when her former producer/self-styled svengali sued both Collette and her record company CBS for ripping off his work. The producer in question had recorded Collette singing Ring My Bell as part of a demo tape and accused CBS of stealing his idea and arrangements. Neither claim held any water in court, much like Collettes career (boooooooom TISH!) and the case was dismissed with the producer having to pay costs. That would have to have hurt. Personally if I was attached to something as awful as Collette’s version of Ring My Bell I’d not be drawing attention to it, I’d be using a pseudonym, such as the name “Jimmy Page”. I’ve seen it done elsewhere. I presume that Andy Scott, he of Sweet fame, still gets asked about those Bucks Fizz singles he wrote and produced, and he might wish that he did – the money wouldn’t hurt.

The case did bring some interesting things to light though, the main facts being that Collette, well, just couldn’t sing a note really and didn’t have much in the way of musical ability. Consider these gems from the trial, all answers from the Main Gal herself:

Q: Yes, but perhaps at least to my ear the version of Ring My Bell that was recorded at Trackdown for example does not bear a great resemblance to the version sung by Anita Ward?

A: That was the best I could do. I am not black and I am not very experienced and I admit that. You know, I took from what I heard by ear and sung it that way like I do with many other songs when I am listening to the radio.

----

Q: In relation to the Anita Ward version. I think you said in that paragraph that you listened to the Anita Ward version four times every night for two weeks?

A: Definitely, and I remember that very clearly because I had to practice before my sister's children went to bed.

----

Now THAT’S dedication to one’s craft. Leaving out the obvious fact, that not even Helen Keller would have mistaken a Vanilla Girl such as Collette for being black, I wonder if those kids could now bring a case before the court for child abuse – imagine having to listen to Collette’s caterwauling four times a night for two weeks solid? It’d be enough to make you turn homicidal, not to mention the damage it’d have wrecked with any musical taste that might have been dormant. The end of case proved a few things though, amongst them:

Anita Ward had a killer voice, with “…considerable vocal agility and range.”

Collette Roberts was a singer who approached Ring My Bell, “…exactly what most people without aspirations to be professional singers do, often more or less inadvertently, if they enjoy 'singing along' with recorded songs.”

Ring My Bell had a lot of, “…colour and variety which Anita Ward was able to give by her singing and which Collette could not reproduce or did not attempt to reproduce, (and) were introduced by other means, as by emphasizing the sound of bells and by having a male voice sing a part of the song.”

There’s a lot more, but hey, read it yourself. As for who had the better song, well just let me say that Anita Ward is on my iPod, Collette isn’t. Ward took an otherwise sappy song and made it into a funky disco classic; Collette took an otherwise sappy song and made it, well weak. Trust me, that does take talent. Still, we shouldn’t be too harsh on Ms Roberts, she does donate her time, and by all accounts she does do more than just throw the occasional apple at a lemur or put some cat chow in for the meerkats at Toronga, and she has given up with the fluro pink bike pants, in public anyway, so we can almost, ALMOST, forgive her for littering the world with her attempts at Ring My Bell. It could have been worse though, have you ever heard Kelly Osbourne bleating through Black Sabbath’s Changes? How bad is it? Ask me to lunch one day, then we’ll sit down for a few hours and I’ll tell you fucking horrible it is. And Paris Stilton’s attempts at ‘singing’ are enough to make a deaf man’s ears bleed in pain. It never ends, and it never will, but sometimes even the most talented of producers can’t polish turds that rank.

---------------------------------------------------------------

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Re: CBS RECORDS AUSTRALIA LIMITED

And: GUY GROSS; GUY GROSS (Cross-Claimant); CBS RECORDS

AUSTRALIA LIMITED (First Cross-Respondent); COLLETTE ROBERTS

(Second Cross-Respondent)

No. G337 of 1989

FED No. 601

Copyright - Restitution

(1989) AIPC para 90-627

And: GUY GROSS; GUY GROSS (Cross-Claimant); CBS RECORDS

AUSTRALIA LIMITED (First Cross-Respondent); COLLETTE ROBERTS

(Second Cross-Respondent)

No. G337 of 1989

FED No. 601

Copyright - Restitution

(1989) AIPC para 90-627

|

| She should have been charged with crimes against fashion |

ORDER

THE COURT DECLARES:

1. that the threats referred to in paragraphs 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 of the Statement of Claim are unjustifiable.

1. that the threats referred to in paragraphs 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 of the Statement of Claim are unjustifiable.

THE COURT ORDERS:

2. that the Respondent be restrained from threatening the Applicant or any other person with any action or proceeding alleging an infringement of copyright in the arrangement or the melody referred to in the Statement of Claim by the performance or broadcasting of the sound recording referred to in the Statement of Claim or by the manufacture or sale of any records embodying the sound recording.

3. that the cross-claim be dismissed.

4. that the Respondent pay the costs of the application and of the cross-claim.

2. that the Respondent be restrained from threatening the Applicant or any other person with any action or proceeding alleging an infringement of copyright in the arrangement or the melody referred to in the Statement of Claim by the performance or broadcasting of the sound recording referred to in the Statement of Claim or by the manufacture or sale of any records embodying the sound recording.

3. that the cross-claim be dismissed.

4. that the Respondent pay the costs of the application and of the cross-claim.

DECISION

These proceedings brought by the applicant, CBS records Australia Limited ("CBS") seek declarations that certain threats made by the respondent, Guy Gross ("Guy") that CBS has infringed the copyright in an arrangement of a musical work of which he was the author were unjustified and seek injunctions to prevent their repetition. In a cross-application brought against CBS and a vocalist, Collette Roberts ("Collette"), Guy seeks relief against the infringement of copyright which he alleges and in which he claims Collette participated. Guy also seeks recompense for work which he claims to have done for Collette and of which he claims Collette took advantage.

In the 1970s, a recording by the American singer, Anita Ward, of the song "Ring my Bell" was released in Australia and became well known in this country. CBS companies overseas had copyright in that work. In 1988, Collette, an aspiring young singer and songwriter, contacted Guy, who was known to her as a person experienced in the writing and composition of songs, to collaborate with her in writing the vocal lines and music of new songs. Thereafter for some time, Collette travelled frequently from her home in Melbourne to Sydney to work with Guy in developing songs. At about this time, Tony Briggs, an employee of CBS, suggested to Collette that, if she wished to obtain a contract with a recording company such as CBS, she ought to record what is called "a cover version" of a song, that is to say her own version of a song which has previously been recorded by another performer. Briggs subsequently gave Collette a tape containing four songs which he suggested would be suitable for cover versions. One of these tracks was "Ring My Bell" sung by Anita Ward.

Collette and Guy decided to record some of the songs which they had written and a cover version of "Ring My Bell". The facilities at Trackdown Studios were booked. Collette and Guy recorded three of their own songs and also "Ring My Bell". Collette sang the vocal lines while Guy produced the instrumental parts using a synthesizer. The tape that was produced was a "demo", that is to say it was of sufficient quality to play to a recording company or a publisher of music but was not of sufficient quality for commercial release.

Subsequently, at Briggs' suggestion, Collette made available to CBS through Briggs a copy of the Trackdown tape which included the new version of "Ring My Bell" ("the Trackdown version"). CBS then offered Collette a contract to sing a version of "Ring My Bell". Collette accepted the contract and the single which was produced, the CBS version, became a successful hit in Australia.

The case put on behalf of Guy is that the Trackdown version was an original work, though an arrangement of the Ward version, that copyright subsisted therein, that Guy was the author of the work and the owner of the copyright therein and that CBS had infringed the copyright by taking, copying and performing a substantial part of that work. CBS denies that the Trackdown version is an original musical work in which copyright subsists, denies that Guy is the author of any copyright therein and denies that it infringed any copyright that might subsist in the Trackdown version.

There is in evidence a tape containing the three versions of the song and I note that in Austin v. Columbia Gramophone Co Ltd at p 409 and Francis Day & Hunter Ltd & Anor v. Bron & Anor at p 594, 608, the importance of aural perception was emphasised. Collette and Guy each gave evidence as to the part each had played in the production of the Trackdown version. Amongst other witnesses, three experts, Dr G.B. Hair, Mr D.L. Williams and Mr M.J. Armiger were called on behalf of Guy and one expert, Mr R.W. Toop, was called on behalf of CBS. In general, for reasons which will become apparent, I prefer the evidence of Collette and Mr Toop to the evidence of Guy and the three experts called on his behalf.

I accept the view of Mr Williams that "the three pieces of composition are uniquely identifiable on account of their different instrumental arrangements." The principal focus of the case is thus the fact that in the Trackdown version and the CBS version Collette is the singer. She is a singer whose voice in its basic characteristics, its range and its capacities, is different from that of Anita Ward. The vocal elements of the Trackdown version and the CBS version are thus similar and markedly different from the vocal part of the Ward version.

In the opinion of Dr Hair, Mr Williams and Mr Armiger, the Trackdown version was an original work and the CBS version is a copy of it. Dr Hair gave this evidence:- "It seems to me for instance that the Anita Ward version is a black funky kind of version probably of an earlier time slightly than the others, and that the later is a sort of white middle class - if I may put it that way - yuppie kind of version. In other words, it has been an attempt to pitch it at a different ambience than the Anita Ward version...I mean, clearly the vocal line is much different. The Anita Ward version attempts - the Anita Ward version if I may say so is a much more subtle version than either of the other two versions in my opinion and I would value it artistically higher than either of the others and that is probably not the question here."

Dr Hair inferred that there must have been a deliberate compositional change:-"Well, it is my judgment that the kind of differences that there are must be a compositional factor rather than simply that the singer did it that way because of some physiological factor or something like that.

...

Well, I would say it is a deliberate attempt to make a different aesthetic type of product."

...

Well, I would say it is a deliberate attempt to make a different aesthetic type of product."

Mr Williams said this in an affidavit:-"In my opinion the Gross version differs significantly from the Anita Ward version particularly in respect of the cognizance it has taken of the singer's tessitura, pitch accuracy, rapidity of articulation, dynamic range and awareness of style. In respect of the singer's tessitura and pitch accuracy it is notable that the overall pitch range of the song in both the Gross version and the CBS version has had to be reduced from 23 semitones to only 10 semitones. It is significant that the amended pitch range of both the Gross version and the CBS version is identical."

Mr Williams concluded:-"The Gross arrangement preserves much of the 'feel' of the original song, but makes changes far too numerous for the two to be considered to be identical arrangements. However it is in my opinion obvious that the CBS version has relied heavily on the modifications to the Anita Ward version which were achieved in the Gross version. There are only four token changes between the Gross version and the CBS version in four separate measures containing the following lyrics:

(a) 'Miss me' (a retrograde inversion of two notes);

(b) 'Dishes' (same as for (a) above);

(c) 'Can rock-a-bye' (transposition up a perfect fourth of Gross modification); and

(d) 'For me and you' (phrase restructure)."

(a) 'Miss me' (a retrograde inversion of two notes);

(b) 'Dishes' (same as for (a) above);

(c) 'Can rock-a-bye' (transposition up a perfect fourth of Gross modification); and

(d) 'For me and you' (phrase restructure)."

Mr Armiger's evidence was as to the same effect. In an affidavit, Mr Armiger said:-“After listening to these versions and examining the musical transcriptions of the melody lines I find that the Gross version differs from the Anita Ward version substantially in that most of the extended notes and phrases have been significantly reduced or altered, probably to accommodate the vocal style or ability of the intended singer.

“I also find that the CBS version is substantially the same as the Gross version and therefore substantially different from the Anita Ward version. It appears, from listening to the Gross version of the song, that some work has been done in adapting the vocal melody to the style, range and capabilities of the singer.

“It further appears, on listening to the CBS version (if this tape was made chronologically later than the Gross version), that the results of this work have been carried on into the CBS version with relatively little further adaptation."

Mr Toop, however, pointed to the fact, with which Messrs Hair, Williams and Armiger agreed in cross-examination, that the Trackdown and CBS versions of the song adopted the melody of the first two lines of the Ward version and repeated it without the elaboration which subsequently appears in Ward version. In his affidavit, Mr Toop said:-"RING MY BELL as it appears in the Sheet Music and as it can be heard in all three versions - in the Trackdown Version, the Anita Ward Version and the CBS Version - is a fairly simple song, using four-by-four 16-bar structures. The overall form is a very simple one, very common in popular music.

“The potentially four-square effect of this structure is somewhat alleviated by the fact

that each line of the verse (and many bars within each four-bar unit) makes use of a

commonly-used device called anacrusis, in which each phrase begins not on the first beat of the first bar of the unit, but on the last beat (known as the 'up-beat') of the preceding bar. The chorus also uses anacrusis, beginning three beats back into the previous bar (i.e. a three-beat 'up-beat'). ... in my opinion the first line of the first verse (third line of the Sheet Music) should be viewed as a simple statement of the basic contour of the verse melody. It uses a limited number of notes within a fairly small compass. Apart from a low G on the word 'you' at the end of the first line, in bar 11, the melody falls within a compass from the B flat below middle C to the G above middle C: the musical interval known as a major sixth. A melody using only this compass should be comfortably within the range of anyone who can sing at all.

“Secondly, once this basic melody line has been set out in line 1 of the song, Anita Ward progressively elaborates this basic line, in keeping with the black American 'funk' vocal tradition to which she apparently belongs.

“Much of what Anita Ward does by way of embellishment can be explained not only in terms of the particular musical tradition to which she belongs, but also by the text of the song. When, as at the beginning of most lines, there are only a couple of syllables in each phrase, there is plenty of scope for syncopation and additional ornamental notes. Where there are many words to sing in a bar (in RING MY BELL this typically happens in the second half of each line), the singer tends to stay on the beat, and there is relatively little scope for syncopation or additional notes. The way Anita Ward overcomes this limitation to her version of the song is by using the ends of lines (in the second verse) to display her considerable vocal agility and range.

“In my opinion the Trackdown Version and the CBS Version as sung by Ms Roberts take what may be called the line of least resistance to the song. That is, both these versions recycle the simplest forms of melody - as presented at the beginning of the Anita Ward Version - as far as possible, and do not attempt to emulate those subsequent embellishments which call for a higher level of rhythmic subtlety, pitching skills, and for a wide vocal compass. Instead of attempting to elaborate the basic melody in terms of a vocal tradition which is not hers, Ms Roberts essentially sings the basic melody on every line of the verse.

“This is by no means an unusual procedure. It is exactly what most people without aspirations to be professional singers do, often more or less inadvertently, if they enjoy 'singing along' with recorded songs. Where the singer on the recording is a professional artist belonging to a sophisticated branch of rock vocal performance such as black American funk, it would be well beyond the capacity of most people to duplicate any but the most basic inflections, syncopations and decorations. Nevertheless, where the song permits it, people can sing along using a simple underlying version of the tune such as that laid down by Anita Ward in line 1 of her version, before she sets about the business of elaboration. In my opinion, doing this does not amount to the creation of an original musical work, irrespective of whether it is done by the 'singing along' singer, or by someone directing that singer.

“I do not disagree that the overall vocal lines of the Trackdown Version and the CBS Version are substantially similar, and that both are substantially different to the Anita Ward Version. However, as I have stated in this Affidavit, I think the vocal lines of both the Trackdown Version and the CBS Version are substantially based, as far as the verses are concerned, on the first line of the Anita Ward Version."

“The potentially four-square effect of this structure is somewhat alleviated by the fact

that each line of the verse (and many bars within each four-bar unit) makes use of a

commonly-used device called anacrusis, in which each phrase begins not on the first beat of the first bar of the unit, but on the last beat (known as the 'up-beat') of the preceding bar. The chorus also uses anacrusis, beginning three beats back into the previous bar (i.e. a three-beat 'up-beat'). ... in my opinion the first line of the first verse (third line of the Sheet Music) should be viewed as a simple statement of the basic contour of the verse melody. It uses a limited number of notes within a fairly small compass. Apart from a low G on the word 'you' at the end of the first line, in bar 11, the melody falls within a compass from the B flat below middle C to the G above middle C: the musical interval known as a major sixth. A melody using only this compass should be comfortably within the range of anyone who can sing at all.

“Secondly, once this basic melody line has been set out in line 1 of the song, Anita Ward progressively elaborates this basic line, in keeping with the black American 'funk' vocal tradition to which she apparently belongs.

“Much of what Anita Ward does by way of embellishment can be explained not only in terms of the particular musical tradition to which she belongs, but also by the text of the song. When, as at the beginning of most lines, there are only a couple of syllables in each phrase, there is plenty of scope for syncopation and additional ornamental notes. Where there are many words to sing in a bar (in RING MY BELL this typically happens in the second half of each line), the singer tends to stay on the beat, and there is relatively little scope for syncopation or additional notes. The way Anita Ward overcomes this limitation to her version of the song is by using the ends of lines (in the second verse) to display her considerable vocal agility and range.

“In my opinion the Trackdown Version and the CBS Version as sung by Ms Roberts take what may be called the line of least resistance to the song. That is, both these versions recycle the simplest forms of melody - as presented at the beginning of the Anita Ward Version - as far as possible, and do not attempt to emulate those subsequent embellishments which call for a higher level of rhythmic subtlety, pitching skills, and for a wide vocal compass. Instead of attempting to elaborate the basic melody in terms of a vocal tradition which is not hers, Ms Roberts essentially sings the basic melody on every line of the verse.

“This is by no means an unusual procedure. It is exactly what most people without aspirations to be professional singers do, often more or less inadvertently, if they enjoy 'singing along' with recorded songs. Where the singer on the recording is a professional artist belonging to a sophisticated branch of rock vocal performance such as black American funk, it would be well beyond the capacity of most people to duplicate any but the most basic inflections, syncopations and decorations. Nevertheless, where the song permits it, people can sing along using a simple underlying version of the tune such as that laid down by Anita Ward in line 1 of her version, before she sets about the business of elaboration. In my opinion, doing this does not amount to the creation of an original musical work, irrespective of whether it is done by the 'singing along' singer, or by someone directing that singer.

“I do not disagree that the overall vocal lines of the Trackdown Version and the CBS Version are substantially similar, and that both are substantially different to the Anita Ward Version. However, as I have stated in this Affidavit, I think the vocal lines of both the Trackdown Version and the CBS Version are substantially based, as far as the verses are concerned, on the first line of the Anita Ward Version."

Collette's evidence accords with Mr Toop's analysis. She gave this evidence:-

Q: What did you ask him (Guy) to do?

A: I asked him if he would like to write some songs with me, co-write, you know, 50/50 on the songs and he said yes and so we started writing together.

Q: I am sorry, your contribution was to be?

Q: I am sorry, your contribution was to be?

A: Well, I wrote the words and melody and I also sang bass lines to him which he would take by ear and put down into his Kurzweil machine.

Q: When you say the words, in the case of Ring my Bell---?

Q: When you say the words, in the case of Ring my Bell---?

A: Well, the words were already there.

Q: And when you say the melody---?

A: Yes.

Q: What do you mean by that?

Q: What do you mean by that?

A: Exactly how the song is, the Ring My Bell, the original. You take the words and the melody. If you change the melody of a song it is no longer Ring My Bell, it is another song. So why would I change the melody of a song or anybody for that matter. Then you would not cover Ring My Bell, you would cover, you make up and write a new song of your own.

Q: Yes, but perhaps at least to my ear the version of Ring My Bell that was recorded at Trackdown for example does not bear a great resemblance to the version sung by Anita Ward?

Q: Yes, but perhaps at least to my ear the version of Ring My Bell that was recorded at Trackdown for example does not bear a great resemblance to the version sung by Anita Ward?

A: That was the best I could do. I am not black and I am not very experienced and I

admit that. You know, I took from what I heard by ear and sung it that way like I do

with many other songs when I am listening to the radio.

Q: But when you say that you took the melody from the original version, the Anita Ward version, are you saying that the Trackdown version has the same melody as the Anita Ward version?

admit that. You know, I took from what I heard by ear and sung it that way like I do

with many other songs when I am listening to the radio.

Q: But when you say that you took the melody from the original version, the Anita Ward version, are you saying that the Trackdown version has the same melody as the Anita Ward version?

A: Definitely. Just the way that I did it was just a bit simple, that is all, but I would not say it is anything different, not for my ear anyway.

Collette said that she practiced by listening to the Anita Ward version. She gave this evidence:-

Q: In relation to the Anita Ward version. I think you said in that paragraph that you

listened to the Anita Ward version four times every night for two weeks?

listened to the Anita Ward version four times every night for two weeks?

A: Definitely, and I remember that very clearly because I had to practice before my sister's children went to bed.

Q: In the course of that listening, that must have been more than fifty times?

Q: In the course of that listening, that must have been more than fifty times?

A: Four times - it is nearly fifty, maybe.

Q: Not terribly similar to the Anita Ward version?

Q: Not terribly similar to the Anita Ward version?

A: Definitely similar because that is the whole idea of doing a cover, because I was

there when I saw Guy Gross take from the Anita Ward tape and put it into his Kurzweil, asking me, 'now we will listen to them both, is the sound similar?' and I would say yes and Guy said no, and he would say 'yes that sounds good,' and that was the way it was.

there when I saw Guy Gross take from the Anita Ward tape and put it into his Kurzweil, asking me, 'now we will listen to them both, is the sound similar?' and I would say yes and Guy said no, and he would say 'yes that sounds good,' and that was the way it was.

Q: There would be no point in doing a cover that was exactly the same as the original?

A: That is the whole idea of doing a cover. The whole idea was just to do a cover of that song as a demonstration tape. There was no need for anything else, that is it.

Collette's evidence finds support in the fact that she was the person who wrote down the words which she had to sing. They were not written down by Guy or notated by Guy. They were written down by Collette. In fact, she made a mistake and misheard the first two words of the song. This mistake was carried through into the Trackdown version, consistent with the point that Collette sang the song as she heard it and as best suited her, leaving substantially to Guy the development of the instrumental backing.

Guy's evidence that he composed the vocal part was not convincing. Guy's work was with the Kurzweil synthesiser and associated equipment. He gave this evidence:-

Q: What you put in the Kurzweil, after listening to the Anita Ward version a number of times, was a synthesised version of the instrumentation of the Anita Ward song?

A: That is not entirely accurate. It was more - certainly it was a synthesiser but it was not just a version. It was not a cut of what was on the cassette. It was created and published on my part, deciphering what was on the cassette and making my own decisions about ---

Q: What you put into the Kurzweil was the instrumental part of the song?

Q: What you put into the Kurzweil was the instrumental part of the song?

A: Of the song as I saw it?

Q: Yes, as you saw it?

Q: Yes, as you saw it?

A: As my version?

Q: Yes?

A: That is right.

Q: You did not put the vocal melody line in the Kurzweil, did you?

Q: You did not put the vocal melody line in the Kurzweil, did you?

A: No.

His evidence provided little more detail in relation to his involvement with the vocal part than that from time to time he cued or pitched the first note of a line for Collette. In an affidavit, Guy said that he rewrote the first two words of the song and that these appeared in the Trackdown version. In cross-examination, however, Guy conceded that the first two words of the song were the result of Collette's error, not of his making.

The tapes themselves support the evidence of Mr Toop and of Collette. Collette sings the basic melody of "Ring My Bell" in a simple direct way. Much of the colour and variety which Anita Ward was able to give by her singing and which Collette could not reproduce or did not attempt to reproduce, were introduced by other means, as by emphasizing the sound of bells and by having a male voice sing a part of the song.

I am left with the impression that, insofar as Collette's vocal lines were concerned, they did not flow from a new composition of which Guy was the author but resulted from the fact that Collette sang "Ring My Bell" as best she could having regard to her style of singing, her limited range, the qualities of her voice and her experience.

As to whether any copyright subsists in the Trackdown version is a point of difficulty. For copyright in an arrangement to subsist, the differences from the work arranged must be such that a new original work can be identified. Differences resulting from mere interpretation, particularly differences brought about by an arrangement of a work to suit the qualities of a particular singer's voice, do not result in the creation of an original work. Particularly is this so in the area of popular music where the latitude given to a performer may be much greater than that in classical works, where the notes, phrasing, emphasis and the like tend to be specified in great detail. Creational composition is required to bring into being an original work.

In Interlego AG. v. Tyco Industries Inc & Ors, the Judicial Committee discussed the elements needed to give copyright protection to a work which was based upon and drew from existing material. Delivering the opinion of their Lordships, Lord Oliver, at p 260-1, cited the comments of Lord Atkinson in Macmillan & Co. Ltd v. Cooper at pp 188, 190:-"It is the product of the labour, skill, and capital of one man which must not be appropriated by another, not the elements, the raw material, if one may use the expression, upon which the labour and skill and capital of the first have been expended. To secure copyright for this product it is necessary that labour, skill and capital should be expended sufficiently to impart to the product some quality or character which the raw material did not possess, and which differentiates the product from the raw material.

“What is the precise amount of the knowledge, labour, judgment or literary skill or taste which the author of any book or other compilation must bestow upon its composition in order to acquire copyright in it within the meaning of the Copyright Act 1911 cannot be defined in precise terms. In every case it must depend largely on the special facts of that case, and must in each case be very much a question of degree."

“What is the precise amount of the knowledge, labour, judgment or literary skill or taste which the author of any book or other compilation must bestow upon its composition in order to acquire copyright in it within the meaning of the Copyright Act 1911 cannot be defined in precise terms. In every case it must depend largely on the special facts of that case, and must in each case be very much a question of degree."

At p 263 Lord Oliver went on to observe:-"... there is no more reason for denying originality to the depiction of a three-dimensional prototype than there is for denying originality to the depiction in two-dimensional form of any other physical object. It by no means follows, however, that which is an exact and literal reproduction in two-dimensional form of an existing two-dimensional work becomes an original work simply because the process of copying it involves the application of skill and labour. There must in addition be some element of material alteration or embellishment which suffices to make the totality of the work an original work. Of course, even a relatively small alteration or addition quantitatively may, if material, suffice to convert that which is substantially copied from an earlier work into an original work. Whether it does so or not is a question of degree having regard to the quality rather than the quantity of the addition. But copying, per se, however much skill or labour may be devoted to the process, cannot make an original work."

When an arrangement is copied or imitated as closely as possible by another performer or performers, the conclusion may, nevertheless, be readily drawn that there is copyright in the arrangement and that that copyright has been infringed: the first because "what is worth copying is prima facie worth protecting" per Peterson J in University of London Press Ltd v. University Tutorial Press Ltd at p 610 and the second because the whole of the arrangement has been taken. See the discussion of "sounds alike music" in The Modern Law of Copyright by Laddie, Prescott & Vitoria para 2.25.

All the witnesses gave most attention to the vocal sounds of the respective versions. Mr Williams and Mr Armiger concentrated their evidence on the vocal lines. Dr Hair, in his evidence, discussed the whole of the work. He thought there were differences both in the instrumental and the vocal parts but said, in the passage set out above "clearly, the vocal line is much different."

Mr Williams pointed out that, in the vocal part of the Ward version of the song, a range of 23 semitones is to be found whereas in the Trackdown version and the CBS version a range of only 10 semitones is to be found. But, if a singer has a limited range, as Collette has, she must reduce the range and must sing those parts of the melody as are within her capacities. As Mr Toop said, this is what every less qualified singer does when singing a song performed by a singer whose range is greater. To take such a step is not to create a new musical work but simply to interpret an existing work having regard to the singer's capability.

Mr Toop thought that originality did not lie in the vocal part of the Trackdown version. As to the instrumental backing, his impression was that in the Trackdown version virtually all of the elements which were involved in the instrumental backing relate to elements found in the Anita Ward version, though that is not to say that they sounded exactly the same. Nevertheless, Mr Toop almost conceded compositional originality in the instrumental backing of the Trackdown version. He gave this evidence:-

Q: And there would be some compositional skill required to go from the first to the

second?

second?

A: There are certain aural skills required to go from the first to the second. Yes, I would say that the act of - and here I am actually referring very specifically to the

instrumental tracks on the Trackdown version - I would say to adapt the rather complex - the more complex resources, instrumental resources of the Anita Ward version to the requirements of simply a synthesiser or whatever else happens to be used, in other words, more modest technical resources, involves certain abilities to reproduce things on a simple scale which is a compositional ability.

Q: What about as between the Trackdown version and the Anita Ward version?

instrumental tracks on the Trackdown version - I would say to adapt the rather complex - the more complex resources, instrumental resources of the Anita Ward version to the requirements of simply a synthesiser or whatever else happens to be used, in other words, more modest technical resources, involves certain abilities to reproduce things on a simple scale which is a compositional ability.

Q: What about as between the Trackdown version and the Anita Ward version?

A: It seems to me that the skills involved to simplify the first parts of the Anita Ward version do not - again, if we - perhaps I should be clear. Are we talking here about the instrumental or the vocal line, because I do regard them as quite separate cases, I must say?

My impression is that the Trackdown version, if considered in its entirety, is the product of sufficient original skill and creative labour to sustain copyright. It is not just a copy of the Ward version. Independent judgment was applied to its creation. Original composition was required for the development of the instrumental backing so as to reflect principal elements of the Ward version yet to match the backing with Collette's style of singing. Were the Trackdown version to be faithfully copied or imitated by other performers, I would find it difficult to say that an original work was not infringed.

But this is not a case where a particular feature stands out, where an opera score has been rewritten for piano or where important new harmonisations have been composed. In the present case, I am unable to identify any such element. Copyright does not subsist in having a singer of Collette's style perform the song, for Collette's voice is not so unusual that its mere use in the song creates an original musical work. Indeed the idea originated with Tony Briggs of CBS. Nor does copyright lie in the development of a present day sound rather than the Anita Ward "funky" ambience for such a change is precisely what many present day singers would be likely to achieve in their interpretation of the song. The originality lies in a myriad of differences, rather than any specific feature, and therefore in the performance as a whole and not in any special or particular feature thereof.

Guy claims to be the owner of the copyright in the Trackdown version. However, he did not work alone on its development. Collette and Guy collaborated together. It was Tony Briggs who suggested the use of a male singer for a part of the song and who introduced that singer. Kirke Godfrey, a sound engineer at the Trackdown studios, made many suggestions and was responsible for the final "mix" of the many individual tracks which had been recorded. Thus, at most, Guy was a joint proprietor of the copyright in the Trackdown version.

Mr D.K. Catterns, counsel for CBS, submitted that, if there were copyright in the Trackdown version, copyright in the instrumental backing resided in Guy and copyright in the vocal part resided in Collette. But the work ought not to be divided in this way. The work was a song having vocal lines and an instrumental backing. There were not two pieces of music. The vocal and instrumental parts were elements which combined together to form a single work. Whether there may be separate copyright in each map of a street directory, as discussed by Hill J. in Universal Press Pty Ltd v. Provest Ltd & Brothers Publishing Pty Ltd (delivered 20 July 1989, unreported) or in each chapter of a novel, as mentioned in University of New South Wales v. Moorhouse & Anor, the present is not such a case.

Mr Catterns also submitted that Guy's claim must fall for the claim presented to the Court was that he had the sole copyright in the work. But it would be wrong to read the pleadings with such precision or to so limit the submissions made. Joint copyright, if infringed, would be sufficient to justify the threats made by Guy to CBS and would also be sufficient to found a grant of relief in favour of Guy. This was accepted by both counsel during the course of the hearing.

The CBS version has points of similarity with both the Ward version and with the Trackdown version. It is therefore necessary to examine with care what parts if any of the arrangement were taken and to examine whether those parts were elements protected by copyright in the Trackdown version.

Sections 13, 14, 31 and 36 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) specify that infringement occurs if a substantial part of a work is reproduced, performed etc. These provisions must be applied in the light of the musical work to be protected. If a work is entirely original, the reproduction or performance of a very small but important part thereof may constitute infringement. See Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd v. Paramount Film Services Ltd. But in the present case, originality does not subsist in a particular element of the Trackdown version, which was itself a cover of the Ward version, but in the multitude of differences which exists between those two works. Infringement must be considered accordingly. To prove infringement it is not sufficient to establish that some of those differences are repeated in the allegedly infringing work. As Lord Pearce said in Ladbroke (Football) Ltd v. William Hill (Football) Ltd at p 293:-"Whether a part is substantial must be decided by its quality rather than its quantity. The reproduction of a part which by itself has no originality will not normally be a substantial part of the copyright and therefore will not be protected. For that which would not attract copyright except by reason of its collocation will, when robbed of that collocation, not be a substantial part of the copyright and therefore the courts will not hold its reproduction to be an infringement. It is this, I think, which is meant by one or two judicial observations that 'there is no copyright' in some unoriginal part of a whole that is copyright."

I am satisfied that CBS did not infringe the copyright. The alleged copying does not reside in the instrumental backing of the CBS version. CBS developed its own instrumental backing and did not copy the Trackdown version. Any similarity between the instrumental parts comes simply from the fact that they were developed at about the same time for the same vocalist and for the same type of audience.

Dr Hair, Mr Williams and Mr Armiger emphasised the similarity between the CBS vocal lines and the Trackdown vocal lines. Between the two there is considerable similarity. But this, of course, results from the fact that the same singer, Collette, in each sings the song in the style best suited to her.

The Trackdown version does not have copyright over Collette's voice. Therefore, when Collette, in the CBS version, sang the song "Ring My Bell" as she had earlier done in the Trackdown version, in a simple, direct way within the normal and limited range of her voice and in her usual style, she was not infringing copyright in the Trackdown version.

Indeed, it is worth noting that Guy did not make a claim for infringement of copyright until three months after the release of the CBS record. On 7 June 1989, his solicitors wrote to CBS:-"... our client assisted in the preparation of the arrangement of the music which is included in a record by Collette Roberts released by your company as a single and called 'Ring My Bell'."

Subsequently, on 16 June 1989, they wrote to CBS's solicitors:-"One further matter which we are now instructed to raise is that we have received advice that the melody sung by Collette Roberts in the song is a melody identical to that on the demonstration tape which was produced and arranged by our client and this melody is absolutely identifiable as original and distinct from the melody which was included in the original song 'Ring My Bell'. Our client will raise this additional matter of copyright in any proceedings he is obliged to commence."

Thus, breach of copyright based upon similarity between the vocal parts of the two arrangements was a late thought.

Mr M G Sexton, counsel for Guy, submitted that copying had necessarily occurred because Collette had learnt the song while developing the Trackdown version and because the sound engineer, Kirke Godfrey, who had worked on the Trackdown version, also assisted in the development of the CBS version. Mr Sexton submitted that Collette and Mr Godfrey must necessarily have been influenced by Guy's ideas and by his input into the composition of the Trackdown version.

However, I am satisfied that CBS set out to achieve and achieved its own arrangement of "Ring My Bell". The principal arranger was Pee Wee Ferris. I accept his evidence, which was not challenged, that he heard the Trackdown version only once and disliked it and, with Kirke Godfrey, decided to create a very different version of the original "Ring My Bell". This they did and the result was a successful hit.

It follows that CBS is entitled to the declaration and injunction which it seeks pursuant to s. 202 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). In this event, CBS does not pursue the claim made for damages under s. 202 of the Copyright Act or orders under ss.80, 82 and 87 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). The cross-claim for an injunction and for damages for infringement of copyright must be dismissed.

The cross-claim further claims the sum of $7,115.00 from Collette for work done and materials supplied. On 29 March 1989, Guy wrote to Collette as follows:-

"Dear Collette,

It was terrific seeing you on MTV last Friday night. An added pleasure for me was to hear you say that due to the demo I produced for you, you have secured a deal, and have been signed up with CBS. Congratulations. Enclosed please find an invoice for the work I have done for you on the demo. I realise that you are not expecting this invoice but by the same token I did not expect you to take my work and pursue your career alone as we had originally agreed to pursue this venture together.

It was terrific seeing you on MTV last Friday night. An added pleasure for me was to hear you say that due to the demo I produced for you, you have secured a deal, and have been signed up with CBS. Congratulations. Enclosed please find an invoice for the work I have done for you on the demo. I realise that you are not expecting this invoice but by the same token I did not expect you to take my work and pursue your career alone as we had originally agreed to pursue this venture together.

I would appreciate prompt attention to this invoice, which will on payment, release you from any other obligations under our initial agreement."

Attached to that letter was an invoice for $7,115.00 which claimed $1225.00, being 35 hours at $35.00 per hour for studio time at Gross Studios, a total of $1890.00 for the hire of three instruments, a Kurzweil, a Macintosh and a Super JX keyboard and $4,000.00 for programming, arranging and producing four songs at $1,000.00 per song.

As Guy's letter foreshadowed, Collette was surprised to receive this invoice for there had been no agreement expressed or implied on her part to pay for work done by Guy or to pay for the hire or use of his studio and equipment. The evidence discloses that Collette and Guy agreed to collaborate in writing songs, that they agreed to record some songs and, at the suggestion of Mr Briggs, agreed to include as one of four songs recorded a cover of an existing work. Both understood that they would receive royalties if their songs were published or performed. That was the reward which Guy anticipated, not any payment by Collette for his contribution. Guy gave this evidence as to the benefit he anticipated from the cover version:-

Q: I suggest you were not happy with the idea of recording a cover version of it because if that were ultimately released you would not get a share of the performance and mechanical royalties?

A: I repeat, I was not unhappy to do that. I in fact realized that by doing this we had more chance of succeeding altogether because, as Collette explained to me, a cover

version is a very appetizing concept for a record company. In that case, even if it was released as a single, there was a hope that one side of the two-sided single would contain an original song?

version is a very appetizing concept for a record company. In that case, even if it was released as a single, there was a hope that one side of the two-sided single would contain an original song?

Q: There was a hope? Yes?

A: Yes.

Q: You would have got half the royalties?

Q: You would have got half the royalties?

A: I would have, had I had a song on the B side.

Q: The B side is the other side of the single?

A: Yes. Further to that: there were discussions with Collette there, hoping

strongly that I would have a side on my B side, a side on the B side of the record.

Q: That would have suited you?

strongly that I would have a side on my B side, a side on the B side of the record.

Q: That would have suited you?

A: It would have been one way of receiving some sort of monetary reward from all this experience, yes.

There was no agreement between Collette and Guy that Collette would not have a career either as a singer or as a songwriter save in association with him and no agreement that Guy would be remunerated by Collette should Collette's career as a singer flourish.

It follows that the claim based upon contract and upon quantum meruit must fail. There was no agreement express or implied for the payment of remuneration.

The claim was also put by Mr Sexton on the footing of unjust enrichment. But there were no circumstances which would make it unfair for Collette to retain any reward she may get as the performer of the CBS version of "Ring My Bell" or otherwise from her singing career. Collette did not do anything unfair in relation to the demo tape produced at the Trackdown studios. It was understood that the tape would be made available to recording studios and others who might wish to take an interest in the songs. Guy himself gave this evidence:-

Q: The intention was that Collette would take the demo tape to music publishers and to record companies to get a publishing deal or a recording deal?

A: The intent was that, yes. There were other intentions but that was one.

Q: And the idea would be if all went well that a record company would sign her up to release records?

A: I would have thought sign both of us up. We both did the work.

Q: But in particular, answering my question, amongst other things to sign Collette up to release records?

Q: But in particular, answering my question, amongst other things to sign Collette up to release records?

A: Amongst other things, yes.

Collette and Guy had copyright in material on the demonstration tape. Had CBS chosen to copy that material, Collette and Guy would have received royalties. But CBS chose not to do so. CBS simply adopted the idea that Collette should do a version of "Ring My Bell", which was in any event the idea of Briggs. There was nothing unjust in what occurred, no reason why Guy should be remunerated by Collette for his work and no reason why Collette should not retain any benefit she may receive from CBS. The cross-claim will therefore be dismissed.

Comments